- Guidance points

- 1 The relationship between embedding and integrating

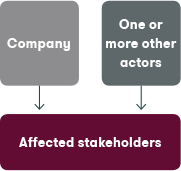

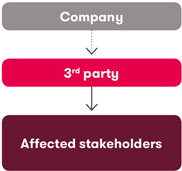

- 2 Understanding how the company is connected to human rights impacts

- 3 The role of leverage

- 4 Exploring different types of leverage

- 5 Identifying opportunities for leverage

- 6 Terminating relationships

- back to top

Introduction

Reading time: 1 minute

The objective of human rights due diligence is to prevent and mitigate impacts on people’s human rights. After identifying their salient human rights issues, companies need to take action to achieve that objective. Prevention and mitigation efforts are forward looking – they are focused on attempting to stop potential impacts from becoming actual impacts. Where this involves third parties, a company’s leverage over those third parties to get them to change their behaviour – and its ability to increase leverage, where necessary – becomes crucial. Where actual impacts do occur, despite efforts to prevent them, then the need for remedy comes into the picture. Remedy is discussed in Chapter 3.8.

Summary of guidance points

Guidance point 1: The relationship between embedding and integrating

Guidance point 2: Understanding how the company is connected to human rights impacts

Guidance point 3: The role of leverage

Guidance point 4: Exploring different types of leverage

Guidance point 5: Identifying opportunities for leverage

Guidance point 6: Terminating relationships

Guidance point 1

The relationship between embedding and integrating

Reading time: 1 minute

Chapter 3.2 explained the importance of embedding the company’s commitment to respect human rights into its organisational DNA. Embedding is the macro-level process of establishing the necessary internal structures, including organising responsibility for human rights and raising awareness among staff of the importance of human rights to their work, so that the commitment translates into a difference in how business gets done.

Integration, by contrast, is the second step in the human rights due diligence process; it is about taking the necessary actions to prevent and mitigate specific human rights impacts at the micro level. This will often involve very different parts of the company. For example, preventing an impact on the right to privacy by end-users of an ICT company’s products requires different action and involves different departments than efforts to mitigate child labour on family farms in a remote part of a food and beverage company’s supply chain.

Guidance point 2

Understanding how the company is connected to human rights impacts

Reading time: 4 minutes

The Guiding Principles recognise that there are different ways in which companies can be involved with human rights impacts, and that the nature of the responsibility to address them is different in each of these scenarios. This is summarised in the table below, which uses OHCHR’s guidance on this topic.47

| Cause | ContributionVariation 1 | ContributionVariation 2 | Linkage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mode of involvement |  |

Contribution through a business relationship. |

Contribution in parallel  |

(...to a company's operations, products or services through a business relationship)

|

| Examples |

|

|

|

|

| Cause | ContributionVariation 1 | ContributionVariation 2 | Linkage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mode of involvement |  |

Contribution through a business relationship. |

Expectations of how companies should respond to involvement with human rights impacts  |

(...to a company's operations, products or services through a business relationship)

|

| Response | Where a company causes a negative human rights impact, it should take the necessary steps to cease or prevent the impact, and remediate it. While addressing such impacts will frequently be within a company’s control, leverage may be relevant in certain instances, such as where a company is under pressure to take actions that would harm human rights (for example, by a government or by the purchasing decisions of a buyer). |

Where a company contributes or may contribute to a negative human rights impact, it should take the necessary steps to cease or prevent its contribution, and use its leverage to mitigate any remaining impact to the greatest extent possible. It should also take steps to ensure the remediation of any actual impact that has occurred. | Where a negative impact is directly linked to a company’s operations, products or services through a business relationship, the company has a forward-looking responsibility to seek to prevent the impact from continuing or recurring. (The business relationship may be a direct one or with an entity more remote in the company’s value chain.) The company has no responsibility under the Guiding Principles to provide remedy for the harm (although it may choose to do so for other reasons). |

|

The nature of a company’s response in each of these three scenarios (cause, contribution, linkage) varies according to:

- Whether the action required is solely forward-looking (linkage), or also includes remedying (or contributing to remedy for) past impacts (cause or contribution);

- Whether the company primarily needs to change its own practices (cause and its own actions in a contribution scenario), or to use leverage to effect change in the practices of a third party (contribution and linkage).

The second table above illustrates the different expected responses. The rest of this section walks through some examples of each scenario in more detail.

Cause

A small restaurant company gets a complaint from customers that the staff in one of its restaurants routinely discriminate against people of a certain race. After some investigation, including hearing from the staff, it finds that the complaints are substantiated. The company should then:

- Take action to prevent further discriminatory practices, for example, by talking with the staff and providing appropriate training, ensuring that any staff who continue with the practice are warned and reprimanded and, if someone refuses to change their behaviour, consider terminating their employment contract (while also taking into account any negative human rights effects that could result from such termination); and

- Put things right with the customers who were discriminated against, for example, through a formal apology, sharing the actions the restaurant’s management have taken to prevent such behaviour in the future, and potentially offering some form of compensation.

Contribution

An apparel company places an order for a large number of T-shirts with a supplier. The company then makes a last-minute change to the type of stitching that it wants the supplier to use. The supplier rushes to ensure that it has the right number of workers available to make the altered design in time to meet the company’s shipping deadline. Because its capacity is stretched, the supplier pressures its workers to work overtime and not to take the days off to which they are entitled in order to meet the order on time.

This is a common scenario in the apparel and footwear sector. A growing number of brand and retail companies have started to review their own purchasing practices to evaluate how they might be contributing to worker abuses at the supplier level through their own last-minute decisions. For example, actions that the US clothing brand, Gap, has taken to try to mitigate this risk include:48

- Working with a smaller, consolidated supplier base and through longer-term relationships that help build a sense of partnership and allow for more honest conversations about the pressures suppliers are under due to the company’s own purchasing practices;

- Collecting data about supplier performance to evaluate where the company can help suppliers build better capacity management systems in their own facilities;

- Developing training for purchasing staff about how their decisions can directly impact workers in supplier facilities to try to avoid such outcomes.

Where an actual situation like the one described above occurs, the UN Guiding Principles also expect the purchasing company to contribute to remedy for the affected workers to the extent of its own contribution to the situation, for example, ensuring that the supplier allows them to claim all the days off they were entitled to and compensating workers directly for the overtime they performed.

Country insights: Turkey

Going 'Beyond audit' to improve human rights standards with suppliers

During the project workshops in Turkey, participants discussed the limits of traditional social compliance programmes and the need for innovative approaches to tackle abuses of workers' riths in supply chains. Participants suggestions included:

- Buying companies should not just "cut and run" when they find an issue, but, rahter, commit to work with their suppliers to improve practices and investing in relationships with them for the long therm;

- Companies should avoid sending conflicting messages to suppliers by pressuring them for fast delivery of high numbers of products on the one hand, while on the other hand setting high expectations for respect for human rights;

- There may be a cultural barrier for suppliers in admitting to mistakes: buying companies should encourage and incentivise suppliers to share their challenges so that they can be jointly addressed;

- Suppliers may need specific support to address certain systemic issues, such as child labour, freedom of association or women's rights.

See also Shift, "From Audit to Innovation: Advancing Human Rights in Global Supply Chains' 2013

Read case story

Linkage

A healthcare company makes compact, portable ultrasound machines, which enable access to life-saving medical treatment in remote regions. In one country where the company sells the machines, there is endemic discrimination against women, leading to strong social preferences for male children. As a result, the company’s machines are used not only to identify and treat actual illnesses and injuries, but also to determine the sex of fetuses to enable early abortion of those that are female. This practice contravenes national law, which also requires manufacturers of such machines to ensure that the practitioners they sell to have government certification to use such machines. However, the law is weakly enforced and the number of female live births has declined.

This was a real situation that GE Healthcare faced in its Indian business. Some of the steps the company took to address the situation, and to ensure the company was not contributing to human rights harms through a failure to take sufficient precautions, included:49

- Stepping up the training provided to all sales agents who sold ultrasound machines, encouraging them to escalate the issue to a manager if they had doubts about a potential practitioner, and making clear that, ultimately, they should not sell the equipment if those doubts could not be addressed;

- Adding explicit warnings about national legal requirements in all sales contracts and in all contracts with dealerships in the country (through which many of their products were sold);

- Posting warnings on the ultrasound machines themselves about the law;

- Engaging with NGOs and other local stakeholders about what actions to take;

- Pushing for industry-wide action on the issue through the Confederation of Indian Industry;

- Collaborating in a public education campaign to raise awareness of women’s and girls’ rights.

Guidance point 3

The role of leverage50

Reading time: 2 minutes

Companies are expected to use leverage where they contribute to an impact together with one or more third parties, or where an impact is linked to their operations, products or services through a business relationship. Leverage is defined as the ability to effect change in the wrongful practices of a third party that causes harm. In other words, leverage is a company’s ability to influence the behaviour of others.

Leverage is at the heart of what companies can realistically be expected to do when faced with complex human rights challenges. A dominant or influential commercial position in a business relationship is likely to help a company’s ability to use leverage. However, many companies are likely to face situations in which they lack such a position and need to think creatively about how to build sufficient leverage.

Companies need to distinguish how they are involved in a human rights impact from their ability to use leverage to address the impact. Company experience shows that when these two discussions get confused, a company’s perception of its responsibility to take action can become tied to whether or not it has obvious leverage.

For example, in one case, a company had identified that it had limited leverage over one of its business relationships and concluded that it, therefore, had no responsibility for human rights harms caused by the business concerned. A more rigorous analysis would have shown that responsibility did exist: there was a linkage between the impacts caused by the third party and the company’s own services. This would have created space for a more constructive discussion within the company of the realities of its limited leverage, as well as encouraging creative thinking about how the company could increase its leverage. Instead, by confusing the issues, the company found itself in a significantdispute with stakeholders over the question of its responsibility and its reputation was harmed as a result.

Companies are very familiar with using leverage in other contexts – for example, in their lobbying efforts with governments. Companies also need to think about these other ways in which they use leverage and consider whether their actions are consistent with their responsibility to respect human rights.

Guidance point 4

Exploring different types of leverage

Reading time: 3 minutes

Ultimately, leverage is about creating the opportunity to change how people think and behave. In the context of the Guiding Principles, it is about changing the thinking and behaviour of key people within a supplier, contractor, business partner, customer, client or government, where that organisation’s actions are increasing risk to human rights. There are many steps a company can take to use leverage that could be as simple as picking up the phone and calling an individual to try to persuade or reason with them to change their approach.

One way to think about the different ways in which a company could exercise leverage is to work through the following types of leverage and think about whether and how each could be relevant in a given situation:

- Traditional commercial leverage: leverage that sits within the activities a company routinely undertakes in commercial relationships, such as contracting.

- Broader business leverage: leverage that a company can exercise on its own but through activities that are not routine or typical in commercial relationships, such as capacity building.

- Leverage together with business partners: leverage created through collective action with other companies in or beyond the same industry.

- Leverage through bilateral engagement: leverage generated through engaging bilaterally and separately with one or more other actors, such as government, business peers, an international organisation or a civil society organisation.

- Leverage through multi-stakeholder collaboration: leverage generated through action collectively with business peers, governments, international organisations and/or civil society organisations.

The following table provides some examples of efforts to use these different categories of leverage; it is not intended to be an evaluation of their effectiveness in practice.

Examples of types of leverage

| Form of leverage | Example | How is leverage built and used? |

|---|---|---|

| A. Traditional commercial leverage |

|

|

| B. Broader business leverage |

|

|

| C. Leverage together with business partners |

|

|

| D. Leverage through bilateral engagement |

|

|

| E. Leverage through multi-stakeholder collaboration |

|

Guidance point 5

Identifying opportunities for leverage

Reading time: 1 minute

It can be helpful to identify specific moments in a business relationship when there may be a particular opportunity to exercise leverage. For example, although a lender may have limited leverage after a loan with a client is agreed, by building a requirement that the client reports on the implementation of an action plan to address human rights impacts, or on the key issues raised through its grievance mechanism, into the covenants attached to the loan, the lender creates an opportunity for follow-up on human rights issues.

Other potential ‘moments of traction’ may include:

- Contract negotiation

- Licensing agreements/renewal

- Setting qualification criteria for bidding processes

- Periodic reports on the implementation of a service or plan of action

- Renewal of service agreements

- Points when services or products require maintenance

- Disbursement of funds

- Monitoring or auditing requirements

- Provision of technical or advisory assistance

- Processes for investigating complaints.

- The severity of the negative impacts involved;

- The extent to which the company has tried to use leverage and/or has run out of options for building further leverage;

- Whether or not the relationship is a crucial one for the company (meaning, does it provide an essential product or service for which no reasonable alternative exists); and

- Whether there would be other negative human rights impacts as a result of ending the relationship.

- Except for ‘contribution in parallel’, the examples are from OHCHR, ‘The Corporate Responsibility to Respect Human Rights: An Interpretative Guide’, 2012, p.17. ↩

- www.gapincsustainability.com ↩

- www.files.gecompany.com ↩

- The following guidance points draw on Shift, ‘Using Leverage in Business Relationships to Reduce Human Rights Risks’, 2013, available at www.shiftprojects.org ↩

- See Voluntary Principles on Security and Human Rights, ‘Model Clauses For Agreements Between Government Security Forces And Companies With Respect To Security And Human Rights’, available at www.voluntaryprinciples.org ↩

- www.akzonobel.com ↩

- www.supply-chain.unglobalcompact.org ↩

- BP, ‘Voluntary Principles on Security and Human Rights: Implementation Guideline’, (pp.8–11): www.bp.com ↩

- www.bettercoal.org ↩

- www.oxfam.org ↩

- www.spiegel.de ↩

- www.bangladeshaccord.org. ↩

- www.rspo.org. ↩

- Reproduced with permission of Shift. ↩

- www.akzonobel.com ↩

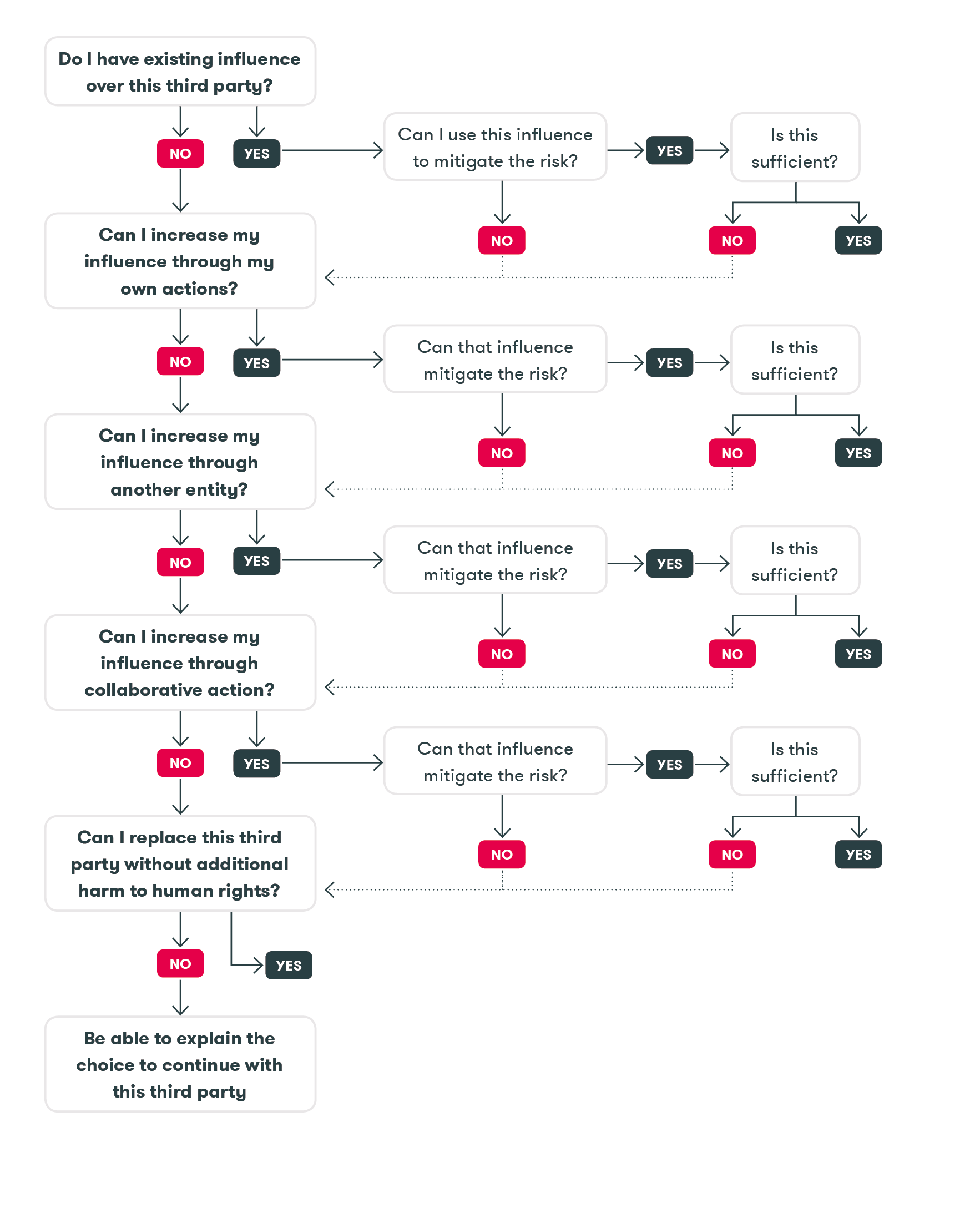

Guidance point 6

Terminating relationships

Reading time: 2 minutes

The Guiding Principles make clear that companies need to think carefully before terminating a business relationship, not least because of the risk of unforeseen negative human rights impacts. For example, if child labour is found in a supplier’s factory and the company simply terminates the relationship, the factory may dismiss the children who may then enter into even riskier forms of work in order to help provide income for their families. This is why leading approaches to child labour do not result in immediate termination of relationships, but, rather, in responses that are informed by the best interests of the child and that seek to protect them – for example, by requiring that the factory continue to pay the equivalent of the child’s wage to their family while the child returns to school until they are of working age.

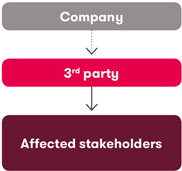

A company needs to consider the following factors when thinking about ending a relationship on human rights grounds:

Building the option for termination on human rights grounds into a relationship right from the start is an important source of leverage in itself, and the threat of termination can, in some cases, be a powerful incentive for improved performance.

The decision tree below sets out how companies might usefully think about these factors in seeking to build and use leverage – and, ultimately, in considering whether to end a relationship.

Learning from practice: AkzoNobel supplier support visits

AkzoNobel, the Dutch-headquartered chemicals company, uses the supplier support visits (SSV)61 programme to provide guidance to suppliers and help them adjust over time to the company’s requirements. The SSV programme is designed to develop long-term local suppliers in emerging markets by raising their capability and performance. According to AkzoNobel, the SSV programme is an important supplier management tool and not an auditing programme. The supportive visits focus on critical suppliers, are announced in advance and are carried out by teams from procurement and health, safety and environment (HSE). The integrated teams request full cooperation from management and ask to see into every corner of the supplier’s factory that they visit.

Formal follow-up visits by these teams are conducted to verify implementation of agreed plans and overall progress. Awareness of, and compliance with, corporate social responsibility is measured with continued support from local, cross-functional AkzoNobel teams. Through the SSV programme AkzoNobel believes that it is able to develop long-term relationships that focus on addressing systemic issues, and suppliers tell the company that being part of the programme brings them recognition in the market and further business opportunities.

Wrapping up

Reading time: 2 minutes

Common pitfalls to avoid

Taking an inconsistent and reactive approach

Often, human rights crises arise and a company struggles to respond. The purpose of human rights due diligence is to develop proactive systems for addressing human rights. When a situation does arise, a company can be prepared with a decision tree or other similar tool for evaluating its involvement with an impact and the corresponding action it is expected to take. Companies can find themselves in trouble when they adopt inconsistent approaches to situations where they are linked to an impact, because they are driven by the priority the business attaches to the relationship, or the particular country context, and not by the severity of the harm and the company’s responsibility to take forward-looking action.

Assuming that you can only be linked to an impact

Human rights due diligence can help a company ensure that it is not contributing to an impact: it can help a company move from a situation of potential contribution to one of linkage. By identifying impacts and seeking to use leverage to mitigate the risk that third parties will continue to cause those impacts, a company can demonstrate that it is meeting its responsibility to respect and is not contributing through its own activities. But this requires ongoing efforts; otherwise, over time, stakeholders will start to question how a company could not have known that an impact was continuing and that its efforts were not proving effective, as has happened, for example, with conflict minerals or child labour in cotton production in Uzbekistan. So companies should not simply assume that just because their initial evaluation is one of linkage, that this will always remain so.

Some suggestions for SMEs

Informal, internal steps can be important

For smaller companies, taking action can often involve informal steps aimed at changing attitudes among staff and making clear that certain behaviour is not an accepted part of the organisation’s culture.

Team up with others

Where a smaller company is linked to a human rights impact through a business relationship, it may be possible to exercise leverage to get that party to change its behaviour where it is also a small enterprise. Where the third party is larger, or much larger, in size, it will be important to team up with others to try to exert leverage. This could involve collaborating with suppliers, customers, business associations, trade unions or public authorities, depending on the situation.

Key sources and websites

Shift and Mazars, UN Guiding Principles Reporting Framework, particularly Part C4

ILO-IOE, 'Child Labour Guidance Tool for Business: How to Do Business with Respect for Children’s Right to be Free from Child Labour', 2015. This guide provides suggestions for due diligence on the specific issue of child labour.

UN Global Compact and Verisk Maplecroft, Human Rights and Business Dilemmas Forum

Oxfam Novib, ‘Multi-stakeholder Engagement in Agribusiness Sectors’, 2015